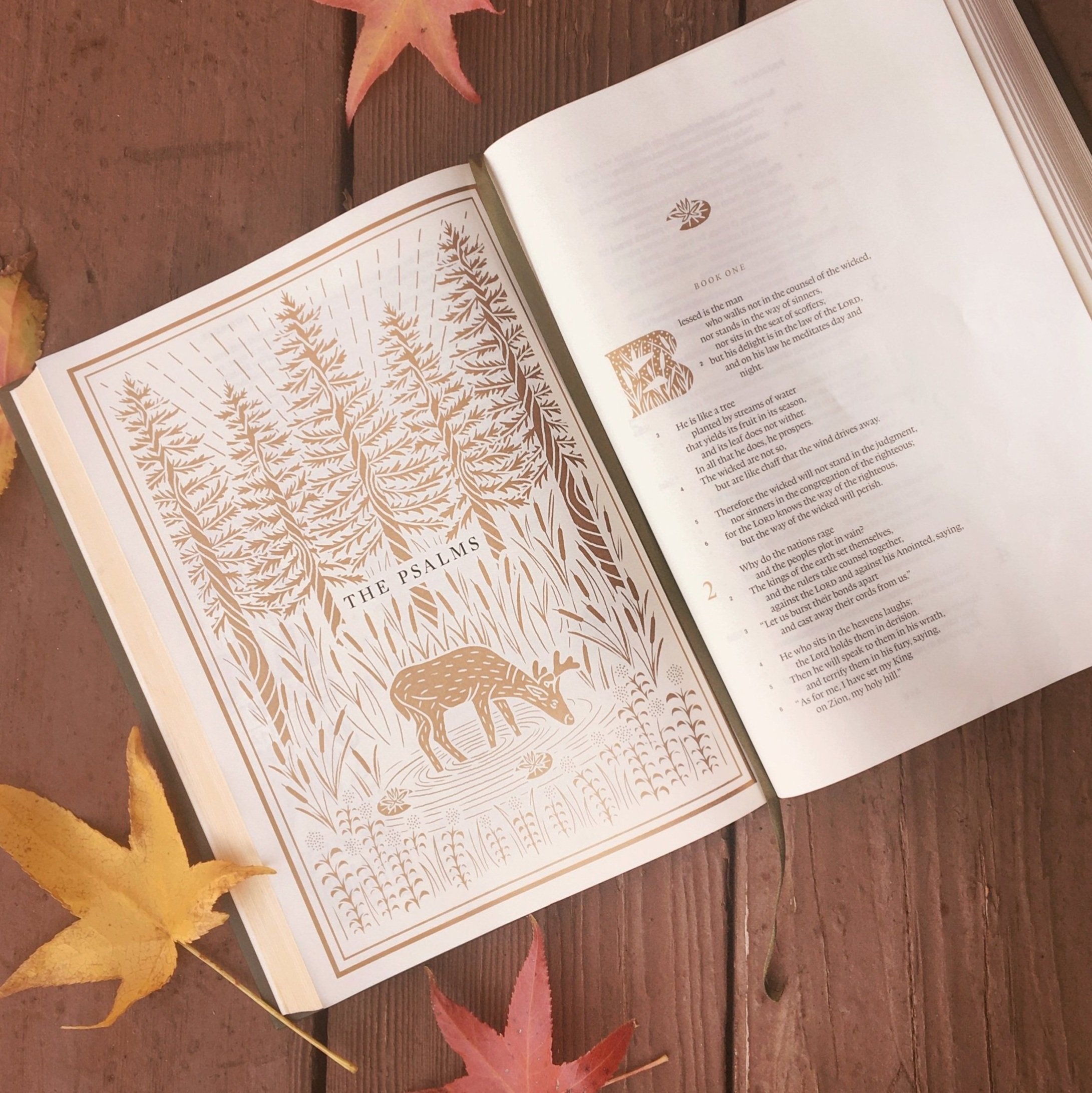

Psalm 1: Walking Trees

As we continue our series on the Psalms, we wanted to take some time to look at Psalm 1 together, which is believed to have been one of the last Psalms to be placed in the Psalter, strategically arranged to serve as an entry point into the rest of the Psalms. Psalm 1 invites us to ask two questions: “What are the Psalms here for?” and “How do we read them?” But more importantly, they ask some fundamental questions of us: “Who are we, and who are we becoming?” and “What is our vision of the good (or virtuous) life?”

Right here at the beginning, the psalmist presents two ways of becoming: the way of the righteous and the way of the wicked, “expressing with remarkable clarity the polarity of persons and their destinies” (Word Bible Commentary Old Testament: Psalms, “Psalm 1,” P.C. Craigie). Blessed is the one who walks in the way of the righteous, the psalmist declares. These are the people who will be like trees planted by streams of water and will yield good fruit, and whose way will be known by the Lord. He begins the psalm with a beatitude, similar to the beatitudes at the beginning of the sermon on the Mount in Matthew 5. The word for “blessed" can be more closely translated as “happy”: happy is the person who walks in the way of the righteous. In our day and age, happiness is a fleeting emotion, usually based on a particular experience.

The Psalms: Our Language of Prayer

Last week, hundreds of thousands of people were without power and electricity for several days across Northern California. It’s currently peak wildfire season, and in an effort to prevent power lines sparking during a windy few days, a major utility company made the difficult decision to cut power in our area. Honestly, it was difficult not to be frustrated during those couple of days — with all the throwing food out of the fridge (and thinking about local businesses who would lose so much money, or families who can’t afford to lose what food they have), stumbling around a dark house with headlamps and candles, showering at a friend’s house who was fortunate enough to have hot water, having to charge my phone in my car, and being without internet access.

You'd have thought that a lack of electricity would have been an encouragement to enjoy being unplugged and unhindered by the distraction of screens for a few days (especially after our recent post on Practices of Resistance!), but I mostly felt oddly disoriented and on edge. Being stuck in darkness for a few days had a disorienting effect on my mind, body, and spirit.

Walter Brueggeman writes about this idea of disorientation in his book Praying the Psalms. He suggests that our faith moves through three phases: “(a) being securely oriented; (b) being painfully disoriented; (c) being surprisingly reoriented” (p. 2). We long for the security of a sense of “equilibrium,” when things feel settled and normal—such as having full access to power, electricity, running water, and internet. While there are some Psalms that reflect this season of secure orientation, but a majority of the Psalms are laments, cries out to God when we experience disorientation.

Rule of Life Book recs

Five of our favorite resources to accompany you as you craft your own Rule of Life

Practices of Resistance: Making Space to Experience God’s Presence

As we continue along in our Rule of Life series and explore spiritual practices that we can integrate into our daily and weekly rhythms, I wanted to introduce a few practices that have been particularly meaningful for both of us in this season. These three practices are specifically geared towards helping us to discern how our use of technology affects our souls:

Turning our phones off for one hour every day.

Reading scripture before looking at our phones when we wake up.

Limiting media intake to a few hours a week.

All three are straight out of Justin Whitmel Earley’s The Common Rule, and he categorizes them as “practices of resistance” because they help us to become aware of how our habits are shaping and forming us, and how we can intentionally resist any habits or messages that are forming us into something other than the image of Christ. He writes,

"Our world is full of a thousand invisible habits of fear, anger, anxiety, and envy that we unconsciously and consciously adopt. Should we do nothing, we will be taught to love the very things that tear us apart. So we must take up the fight, open our eyes to the way media form us in fear and hate, the way screens form us in absence, and see the way excess and laziness train us to love ourselves above all else. But remember that resistance has a purpose: love. The habits of resistance aren’t supposed to shield you from the world but to turn you toward it. They aren’t so you can feel good about you’ve done for you. They exist so you can feel peace about what God has done for you” (The Common Rule, 25).

Sabbath Rest

We live in a culture that equates busyness with significance. We’re defined by what we do, so we avoid the Sabbath because we don’t want to acknowledge our limits as human beings. We’re constantly attempting to prove our worth to ourselves and to others. I’m struck by Eugene Peterson’s observations about two underlying narratives behind our busyness:

“I’m busy because I am vain. I want to appear important.”

“I am busy because I am lazy. I indolently let others decide what I will do instead of resolutely deciding myself” (The Contemplative Pastor).

Ouch. Stopping our “doing” would mean facing something we’re perpetually trying to avoid—feeling insignificant, unseen, or unimportant. Susan Phillips quotes one of her directees in The Cultivated Life: “I fear stopping because then I will feel regret for the emptiness of my days.” Double ouch.

Rule of Life: An Intro to a Lifelong Spiritual Practice

I was first introduced to the concept of a “rule of life” when I was in seminary. I was taking a week-long intensive course on “Spiritual Traditions and Practices,” and one of our assignments was to write our own rule of life for the following six months. In my ambition, I crafted a list of daily, weekly, and monthly spiritual practices that I thought would impress my professor, from reading all of C.S. Lewis’ collected works to watercolor painting every week, to praying a psalm a day. Then real life happened, and I’m not sure I looked at again, even once.

The word “rule” may not sound all that appealing—especially when it’s attached to the words “OF LIFE.” Does writing one mean I have to follow every single practice for the rest of my days?

Well, if you’re anything like me, then there’s some good news: the word “rule” isn’t referring to set of near-impossible expectations or standards to uphold at all! Rather, a rule of life is simply a curated set of intentional practices and rhythms that cultivate attentiveness to God in this specific season of your life.

The Listening Life: A Book Review (and a special event!)

Adam McHugh’s take on developing a life of listening to God, others, and ourselves

Sacred Conversations

We are changed as we are known. And when it comes to words and transformation, we are known by what we share and reveal about ourselves. You see, speaking the truth in love isn’t just about the receiver or listener being changed, the one who hears the truth spoken in love—it’s also the one speaking who is changed. Conversations around connection and self-revelation change both the speaker and the listener.

Curt Thompson describes what the process of Romans 12:2 ("be transformed by the renewing of your mind”) looks like from a neuroscience perspective. He unpacks all the different parts of the brain and how they function separately and together, and his conclusion is that as we engage in healthy conversation for the purpose of connection and communion, our neural networks undergo physical changes. Sharing our stories in deep, meaningful conversation in a safe relationship actually creates new neural pathways that can lead to healing and freedom.

We are physically and neurologically changed by sacred conversations. The deep soul-and-spirit change we feel in these conversations is confirmed by the change in our brain chemistry. Words spoken in love have the power to transform every part of who we are—the spiritual, the emotional, the relational, the mental, and the physical. That is extraordinary to me!

Asking Questions as a Spiritual Practice

While we can certainly find answers to some of our deepest questions in scripture, we can also find the freedom to sit with our questions before the Father. Jesus Himself posed seemingly simple yet profoundly provocative questions, like “Who do you say that I am?” (Matthew 16:15), and “What do you want me to do for you?” (Mark 10:36 and 51) or “Do you want to get well?” (John 5:6). Even the questions asked of Jesus hold a weightiness, such as the question of theodicy that the disciples pose to Jesus when they encounter a man who was blind since birth: “Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?” (John 9:2). Spend any amount of time in just one of the Gospels, and you’ll find any number of such questions!

So, how can asking sacred questions become a spiritual practice, and what can they do in your spiritual life, you might ask?